Could You Maybe Possibly Explain Indirect Speech Acts?

My work in the human-robot interaction laboratory focuses on making dialogue between humans and robots as natural as possible.

There’s been a lot of cool work into allow robots to understand simple statements like:

- “Go to the kitchen”

- “Drive forward”

- “Bring me a beer”

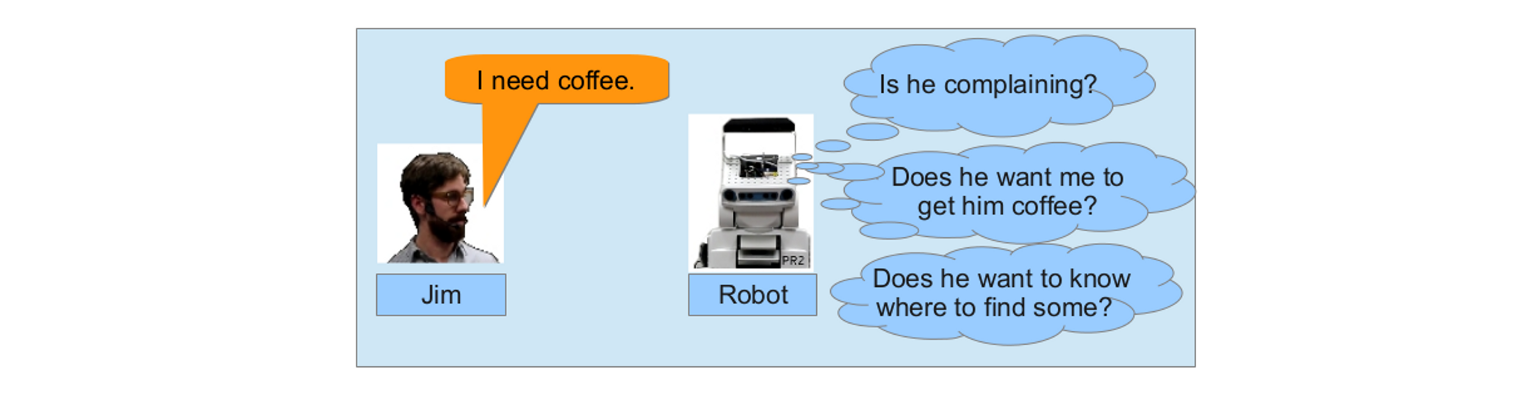

Unfortunately, most human language is significantly more complicated. Consider the utterance “I need a coffee”. Understanding this utterance is significantly more complex, because you can’t determine its meaning just by looking at it!

Why what DOES this mean?!

Why can’t you determine what “I need a coffee” means by just looking at it? Naively inspecting this sentence merely suggests that it is a bit of musing about one’s state of mind, and that if a robot hears such a phrase, it should perhaps respond “how interesting!”.

It’s highly unlikely that this was the speaker’s intention! In order to figure out what they actually intended, we must consider the robot’s context.

- Is the speaker friends with the robot? The speaker might be complaining.

- Did the speaker just put their coat on? The speaker might be suggesting the robot accompanying him to go acquire coffee.

- Is the robot working as a barista? The speaker might be ordering coffee.

This one sentence could imply (at least) three different things depending on context? All this ambiguity could be easily avoided by simply being direct about what we’re trying to communicate! Right? Let’s try that out.

- “I am very tired and need coffee. Sympathize with me and say something encouraging!”

- “I am going to go get coffee. Come with me.”

- “Give me coffee”

Yikes. Being direct like this would be perceived as weird, if not outright rude. Hence our use of less direct forms of communication, i.e., indirect speech acts.

Indirect Speech Acts

An indirect speech act (or ISA) is an utterance whose literal meaning mismatches with its intended meaning. Here are some more examples of ISAs:

- Do you know what time it is? (Usually not a real question.)

- Could you pass the salt? (Usually not a real question.)

- It’s cold in here… (Not an idle comment if your boss is gesturing towards the open window!)

Handling Indirect Speech Acts

Alright, so we’ve defined indirect speech acts. How do we determine the intention underlying an utterance

in a particular context? There are two main approaches to understanding indirect speech acts: the idiomatic approach,

which can handle ISAs that follow an idiomatic form (e.g., “Could you [whatever]”), and the inferential approach, which

can handle ISAs such as “It’s cold in here” by considering the speaker’s goals and intentions, and reasoning about what

actions they might want you to take (e.g., closing the damn window!) in service of those goals and intentions.

which uses an idiomatic approach.

The Rule List

At the heart of our algorithm is the rule list. Each rule in this list maps a particular utterance to a particular intention under a particuplar context. Let’s say you want to be able to perform the following inference:

“If Julie tells me she needs coffee, and she thinks I’m a barista, then I’ll assume she intended to communicate that she wants me to give her coffee.”

First, let’s break this into its constituent parts.

- The Utterance: Julie tells me she needs coffee

- The Context: Julie thinks I’m a barista

- The Intention: Julie wants me to give her coffee

This is a great start, but is this scenario really Julie-specific, or even specific to me?

If anyone tells someone they think to be a barista that they need coffee,

isn’t it a good bet that they want that person to give them some coffee?

We thus generalize the rule in the following way.

- The Utterance: Statement(from X to Y): X needs coffee

- The Context: Belief (of X): Y is a barista

- The Intention: Intention (of X): Y should give X coffee

How do we use this rule? Well, if we hear someone say they need coffee, and we believe that they believe that the person they are talking to (who may or may not be us) is a barista, then we can assume that the speaker wants the person they’re talking to to give them coffee. And if they’re talking to us, and we’re obliged to give them coffee, then we’d better well do it!

Some previous systems essentially perform this inference process using a whole list of rules. When the robot hears an utterance, it looks through the list and find all rules whose utterance matches the utterance they heard, and whose contextual items are all currently true (e.g., the robot actually thinks that the speaker thinks the robot is a barista). The previously described inference process is performed on each matching rule, and the intentions that result from those matching rules are then examined.

Unfortunately, real life is rife with uncertainty. Sometimes you aren’t completely certain of what people say. Or think. Or what their obligations are. Or what your obligations are. Or what anything means, anyways. We thus need some way to process these rules under all this uncertainty!

Wait, what did you say? Who are you?

Who am I? What does it all mean?!

In order to represent our certainty about, well, anything, we use some concepts from The Dempster-Shafer Theory of Evidence.

Wait! Don’t run away! I promise this won’t be scary.

Dempster-Shafer Theory is an extension of standard probability theory that has some really nice properties that I won’t

get into now, but which I could easily detail in another blog post.

Let’s say we want to consider how certain we are that our friend Julie thinks we’re a barista. We represent this information using two numbers: our belief that Julie thinks we’re a barista, and the plausibility that Julie thinks we’re a barista. These two numbers are written like this [belief, plausibility] (e.g., [0.5,0.6]). Both numbers are always between zero and one, and belief is always less than or equal to plausibility.

The belief represents the weight of all evidence for Julie thinking we’re a barista, and the plausibility is one minus the weight of all evidence against Julie thinking we’re a barista.

Let’s say we’re in a Starbucks, and I’m wearing a starbucks uniform. This is pretty strong evidence I’m a barista. Let’s arbitrarily say this constitutes a weight of 0.7. Let’s also say that I’m waiting in line at this starbucks. This might suggest I’m not a barista. Let’s aribitrarily say this constitutes a weight of 0.2. We could then represent our certainty that Julie thinks I’m a barista using the interval [0.7,0.8]. Note that there’s a little gap between these two numbers. this represents the ignorance in the situation. Let’s say I wasn’t wearing the uniform. The interval would then be [0.0,0.8] - there’s nothing to suggest I am a barista, but in the end there’s not that much evidence suggesting I’m not.

The larger the gap between belief and plausibility, the more ignorant we are of the truth of the hypothesis in question. The closer the center of the gap is to 0.5, the more ambiguous the situation is (as there’s closer to being equal weight for and against the hypothesis in question).

Uncertain Logical Inference

So we have a representation of uncertainty. Great. How do we use it?

Essentially, an interval of this type is attached to

each incoming utterance, each piece of knowledge, and each rule. Then, when the robot hears an utterance, it follows the

following steps to determine what was meant by that utterance.

1) For each rule in the rule base whose utterance matches the current utterance (to some degree) and whose contextual items are believed to be true (to some degree), we first perform an uncertain logical AND on utterance and context. Essentially, this means we combine (a) our certainty that the utterance we heard is the same as the utterance attached to the rule we’re looking at, with (b) our certainty that each of the rule’s contextual items are true. This will produce (c) an overall measure of our certainty that this rule is applicable.

We then use uncertain modus ponens. This essentially combines this new overall certainty measure with the certainty interval associated with the rule itself (which specifies how sure we are that the rule is even accurate), and produces a new uncertainty interval which is associated with the rule’s intention, that is, it tells us how sure we should be that the speaker meant to communicate whatever is on the rule’s intention line.

2) If multiple rules produce different information about the same intention (perhaps for entirely different reasons), the disparate uncertainty intervals produced by those rules are fused together using a method such as Yager’s Rule of Combination. We should now have a set of unique intentions possibly communicated by the utterance the robot heard, each of which is attached with an interval reflecting our certainty in that intention.

The Aftermath

Once we’ve got this set of intentions, what do we do with it? Well, if the robot is confident in all of the intentions, they are inserted into memory. For example, if the robot is confident that Julie wants it to give her coffee, it will store this fact in memory, and may or may not actually get Julie her coffee. If the robot isn’t certain what was intended by the speaker’s utterance, it can ask for clarification.

Give us some kind of clue!

To determine if a robot is uncertain enough to ask for clarification, we use Nunez’ Uncertainty Measure, which analyzes an uncertainty interval and returns a number that reflects the uncertainty reflected by the interval: the more ambigity or ignorance, the lower the value. If, for a particular intention, the value returned by this uncertainty measure is less than some threshold (e.g., 0.1), the robot will ask for clarification regarding that intention. The robot can then act based on the results of that clarification request. And, in principle (although not yet integrated into our algorithm), the robot could then modify its certainty in the pragmatic rules it used, so that it will be less likely to need to ask for clarification on future utterances of the same sort.

One of my favorite examples of clarification requests and subsequent adaptation in resolution of indirect speech acts actually comes from Star Trek: The Next Generation, in the episode “Interface”.

DATA: Are you certain you do not wish to talk about your mother?

GEORDI: Why do you ask that?

DATA: You are no doubt feeling emotional distress as a result of her disappearance. Though you claimed to be “just passing by,” that is most likely an excuse to start a conversation about this uncomfortable subject. Am I correct?

GEORDI: Well, no. Sometimes “just passing by” means “just passing by.”

DATA: Then I apologize for my premature assumption.

…

GEORDI: Data, maybe you gave up too fast.

DATA: I do not understand.

GEORDI: When I said “just passing by” means “just passing by,” I didn’t really mean it.

DATA: My initial assumption was correct. You do wish to speak of your mother.

What I’ve described here is the gist of the paper I presented at IBERAMIA last week. If you’re interested in delving into the details, you can find the full paper here. Since that paper was accepted, we’ve done a lot to advance this research project. Most importantly, we’ve (1) added the ability to generate ISAs (in addition to just understanding them), and (2) fully integrated our algorithms into our robot architecture, DIARC. I’ll be presenting a paper on these and other advancements at one of the main AI conferences (AAAI) in late January.

Leave a Comment